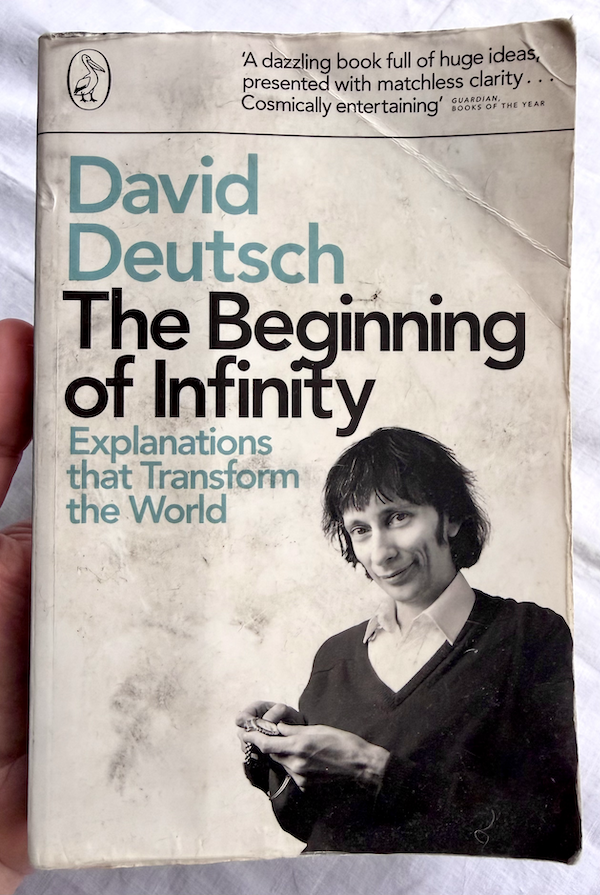

Recommendation strength: 10/10

Recommendation strength: 10/10

Recommendation strength: 10/10

Recommendation strength: 10/10

You should read this if:

Your phone is set to silent, you have prepared a large flask of coffee, and have readied your favourite armchair for many hours of deep reflection on what knowledge is, how it’s created, and its infinite capability to solve problems.

My thoughts:

Formidably erudite and yet eminently readable, Deutsch helped me become more tolerable in conversation through his convincing account of the virtues of fallibilism (i.e. the recognition that there are no authoritative sources of knowledge, nor any reliable means of justifying ideas as being true or probable). “Fallibilists expect even their best and most fundamental explanations to contain misconceptions in addition to truth, and so they are predisposed to try to change them for the better.” Too often I find myself vehemently defending positions that I have (sometimes knowingly, but more often subconsciously) lifted directly from sources of authority that I trust and that align with my worldview. But nobody wants to debate someone unprepared to entertain ideas that challenge their own. Isn’t it more energising to speak with someone open-mindedly and genuinely curious to rectify their inevitable misconceptions? Rather than asserting misconceptions as facts, what I should be doing is seeking good explanations. That’s what this book is about.

A good explanation is hard to vary while still accounting for what it purports to account for. Put another way, the structure of a good explanation cannot be changed without affecting its ability to make sense of the phenomenon it seeks to explain. In contrast, “the seasons are the result of an ongoing battle between the fire god and the ice god” is a bad explanation, because the battle could easily be replaced with “the sun god becomes angry with humans each year and refuses to raise the sun high in the sky, causing winter,” without loss of explanatory power. The axial tilt theory of the Earth is a good explanation because it is hard to vary in this structural sense. Changing from a tilted rotation axis to one perpendicular to the orbital plane would break the explanation’s explanatory power, as a vertical rotation axis would result in consistent local weather year-round (i.e., no seasons). Good explanations require both creativity (making guesses that can be exposed to criticism) and criticism (testing those guesses with logic, reason, or experimentation).

Creating good explanations contributes to the growth of knowledge, and there is no known limit to what knowledge created in this way can explain, and therefore achieve. In Deutsch’s words: “if something is permitted by the laws of physics, then the only thing that can prevent it from being technologically possible is not knowing how.” We also need sufficient time, resources, and error correction, but this is the basis for his assertion that optimism is rational, and that most evils persist through insufficient knowledge. Far from arguing blind faith that “things will work out” is rational, this is a recognition that problems are inevitable, but soluble. It is not an argument that optimism guarantees progress or success within a given timeframe, avoidance of risk or suffering, or is morally ‘good’.

Given the prevalence of compellingly-clickable apocalyptic and prophetic headlines, it is tempting to lament present-day challenges as inherently insurmountable, but this is a fallacy. With the right knowledge, time, and resources, we can resolve any problem that is not prevented by the laws of physics. This fundamentally changed my mindset. Deutsch explains: “society is not a zero-sum game: the civilization of the Enlightenment did not get where it is today by cleverly sharing out the wealth, votes or anything else that was in dispute when it began. It got here by creating ex nihilo.” Problems lead to new problems, but that should not lead to despair. We grow the pie by solving problems. To expect that solutions will always be found in time to avert disasters is a fallacy, but so is giving up hope altogether. The burden of proof for justifying pessimism is much higher than for optimism. We shouldn’t mistake “we don’t currently know how” for “it can’t be done”. Even failed attempts at creating good explanations create knowledge (i.e. of what doesn’t work).

Other extracts from the book which challenged my beliefs include:

- “Changing our genes in order to improve our lives and to facilitate further improvements is no different in this regard from augmenting our skin with clothes or our eyes with telescopes.”

- “Biological evolution does not optimize benefits to the species, the group, the individual or even the gene, but only the ability of the gene to spread through the population.” (I’ve added The Selfish Gene to my reading list)

- “Like scientific theories, policies cannot be derived from anything. They are conjectures. And we should choose between them not on the basis of their origin, but according to how good they are as explanations: how hard to vary.”

- “The evil of death - that is to say, the deaths of human beings from disease or old age. This problem has a tremendous resonance in every culture - in its literature, its values, its objectives great and small. It also has an almost unmatched reputation for insolubility (except among believers in the supernatural): it is taken to be the epitome of an insuperable obstacle. But there is no rational basis for that reputation. It is absurdly parochial to read some deep significance into this particular failure, among so many, of the biosphere to support human life - or of medical science throughout the ages to cure ageing. The problem of ageing is of the same general type as that of disease. Although it is a complex problem by present-day standards, the complexity is finite and confined to a relatively narrow arena whose basic principles are already fairly well understood.”

- “Even different electrons do not have complete separate identities.”

- “When a piece of music has the attribute ‘displace one note and there would be diminishment' there is an explanation: it was known to the composer, and it is known to the listeners who appreciate it” ... “if I am right, then the future of art is as mind-boggling as the future of every other kind of knowledge: art of the future can create unlimited increases in beauty.”

This book is dense with insight. I’ll admit that I found many concepts challenging, but with liberal use of LLMs to provide alternate explanations, I finished each chapter with at the very least a little intellectual morsel to chew on over the subsequent days. I’ll be revisiting this book in a few months, or years, when the torrent of steam that is currently emanating from the skin above my poor, overworked prefrontal cortex has dissipated, and I have nourished and rejuvenated my mind with a few gentle novels.

Extracts:

But, in reality, scientific theories are not 'derived' from anything. We do not read them in nature, nor does nature write them into us. They are guesses - bold conjectures. Human minds create them by rearranging, combining, altering and adding to existing ideas with the intention of improving upon them.

Discovering a new explanation is inherently an act of creativity.

The deceptiveness of the senses was always a problem for empiricism - and thereby, it seemed, for science. The empiricists' best defence was that the senses cannot be deceptive in themselves. What misleads us are only the false interpretations that we place on appearances. That is indeed true - but only because our senses themselves do not say anything. Only our interpretations of them do, and those are very fallible. But the real key to science is that our explanatory theories - which include those interpretations - can be improved, through conjecture, criticism and testing.

The recognition that there are no authoritative sources of knowledge, nor any reliable means of justifying ideas as being true or probable – is called fallibilism.

Fallibilists expect even their best and most fundamental explanations to contain misconceptions in addition to truth, and so they are predisposed to try to change them for the better.

But one thing that all conceptions of the Enlightenment agree on is that it was a rebellion, and specifically a rebellion against authority in regard to knowledge.

This is why the Royal Society (one of the earliest scientific academies, founded in London in 1660) took as its motto 'Nullius in verba', which means something like 'Take no one's word for it.'

What was needed for the sustained, rapid growth of knowledge was a tradition of criticism.

One consequence of this tradition of criticism was the emergence of a methodological rule that a scientific theory must be testable (though this was not made explicit at first). That is to say, the theory must make predictions which, if the theory were false, could be contradicted by the outcome of some possible observation. Thus, although scientific theories are not derived from experience, they can be tested by experience - by observation or experiment.

In general, when theories are easily variable in the sense I have described, experimental testing is almost useless for correcting their errors. I call such theories bad explanations. Being proved wrong by experiment, and changing the theories to other bad explanations, does not get their holders one jot closer to the truth.

The quest for good explanations is, I believe, the basic regulating principle not only of science, but of the Enlightenment generally.

But the difference is, if the axis-tilt theory had been refuted, its defenders would have had nowhere to go. No easily implemented change could make tilted axes cause the same seasons all over the planet. Fundamentally new ideas would have been needed. That is what makes good explanations essential to science: it is only when a theory is a good explanation - hard to vary - that it even matters whether it is testable. Bad explanations are equally useless whether they are testable or not.

Some people become depressed at the scale of the universe, because it makes them feel insignificant. Other people are relieved to feel insignificant, which is even worse. But, in any case, those are mistakes. Feeling insignificant because the universe is large has exactly the same logic as feeling inadequate for not being a cow. Or a herd of cows. The universe is not there to overwhelm us; it is our home, and our resource. The bigger the better.

Perhaps it is the mistaken empiricist ideal of 'pure', theory-free observation that makes it seem odd that truly accurate observation is always so hugely indirect. But the fact is that progress requires the application of ever more knowledge in advance of our observations.

80 per cent of that matter is thought to be invisible 'dark matter', which can neither emit nor absorb light. We currently detect it only through its indirect gravitational effects on galaxies. Only the remaining 20 per cent is matter of the type that we parochially call 'ordinary matter'. It is characterized by glowing continuously. We do not usually think of ourselves as glowing, but that is another parochial misconception, due to the limitations of our senses: we emit radiant heat, which is infrared light, and also light in the visible range, too faint for our eyes to detect.

The ancestor species of humans colonized new habitats and embarked on new lifestyles in exactly that way. But by the time our species had evolved, our fully human ancestors were achieving much the same thing thousands of times faster, by evolving their cultural knowledge instead. Because they did not yet know how to do science, their knowledge was only a little less parochial than biological knowledge. It consisted of rules of thumb. And so progress, though rapid compared to biological evolution, was sluggish compared to what the Enlightenment has accustomed us to.

Since the Enlightenment, technological progress has depended specifically on the creation of explanatory knowledge. People had dreamed for millennia of flying to the moon, but it was only with the advent of Newton's theories about the behaviour of invisible entities such as forces and momentum that they began to understand wha was needed in order to go there.

every putative physical transformation, to be performed in a given time with given resources or under any other conditions, is either - impossible because it is forbidden by the laws of nature; or - achievable, given the right knowledge. And so, again, everything that is not forbidden by laws of nature is achievable, given the right knowledge.

In some environments in the universe, the most efficient way for humans to thrive might be to alter their own genes. Indeed, we are already doing that in our present environment, to eliminate diseases that have in the past blighted many lives. Some people object to this on the grounds (in effect) that a genetically altered human is no longer human. This is an anthropomorphic mistake. The only uniquely significant thing about humans (whether in the cosmic scheme of things or according to any rational human criterion) is our ability to create new explanations, and we have that in common with all people. You do not become less of a person if you lose a limb in an accident; it is only if you lose your brain that you do. Changing our genes in order to improve our lives and to facilitate further improvements is no different in this regard from augmenting our skin with clothes or our eyes with telescopes.

the trick of extracting oxygen from moon rocks depends on having compounds of oxygen available. With more advanced technology, one could manufacture oxygen by transmutation; but, no matter how advanced one's technology is, one still needs raw materials of some sort. And, although mass can be recycled, creating an open-ended stream of knowledge depends on having an ongoing supply of it, both to make up for inevitable inefficiencies and to make the additional memory capacity to store new knowledge as it is created.

Likewise, because humans are universal constructors, every problem of finding or transforming resources can be no more than a transient factor limiting the creation of knowledge in a given environment. And therefore matter, energy and evidence are the only requirements that an environment needs to have in order to be a venue for open-ended knowledge creation.

at present during any given century there is about one chance one in ten thousand that the Earth will be struck by a comet or asteroid large enough to kill at least a substantial proportion of all human beings. That means that a typical child born in the United States today is more likely to die as a result of an astronomical event than a plane crash.

in addition to threats, there will always be problems in the benign sense of the word: errors, gaps, inconsistencies and inadequacies in our knowledge that we wish to solve - including, not least, moral knowledge: knowledge about what to want, what to strive for. The human mind seeks explanations; and now that we know how to find them, we are not going to stop voluntarily. Here is another misconception in the Garden of Eden myth: that the supposed unproblematic state would be a good state to be in. Some theologians have denied this, and I agree with them: an unproblematic state is a state without creative thought. Its other name is death.

The evidence of apparent design for a purpose is not only that the parts all serve that purpose, but that if they were slightly altered they would serve it less well, or not at all. A good design is hard to vary ... Merely being useful for a purpose, without being hard to vary while still serving that purpose, is not a sign of adaptation or design. For instance, one can also use the sun to keep time, but all its features would serve that purpose equally well if slightly (or even massively) altered.

Any theory about improvement raises the question: how is the knowledge of how to make that improvement created? Was it already present at the outset? The theory that it was is creationism. Did it 'just happen'? The theory that it did is spontaneous generation.

The fundamental error being made by Lamarck has the same logic as inductivism. Both assume that new knowledge (adaptations and scientific theories respectively) is somehow already present in experience, or can be derived mechanically from experience. But the truth is always that knowledge must be first conjectured and then tested.

Therefore the existence of an unsolved problem in physics no more evidence for a supernatural explanation than the existence of an unsolved crime is evidence that a ghost committed it.

False explanations of biological evolution have counterparts in false explanations of the growth of human knowledge.

Biological evolution does not optimize benefits to the species, the group, the individual or even the gene, but only the ability of the gene to spread through the population.

But it is no mystery where our knowledge of abstractions comes from: it comes from conjecture, like all our knowledge, and through criticism and seeking good explanations. It is only empiricism that made it seem plausible that knowledge outside science is inaccessible; and it is only the justified-true-belief misconception that makes such knowledge seem less 'justified' than scientific theories ... Experimental testing is only one of many methods of criticism used in science

Certainly you can't derive an 'ought' from an 'is', but you can't derive a factual theory from an 'is' either. That is not what science does. The growth of knowledge does not consist of finding ways to justify one's beliefs. It consists of finding good explanations. And, although factual evidence and moral maxims are logically independent, factual and moral explanations are not. Thus factual knowledge can be useful in criticizing moral explanations.

Knowledge is information which, when it is physically embodied in a suitable environment, tends to cause itself to remain so.

What Achilles can or cannot do is not deducible from mathematics. It depends only on what the relevant laws of physics say. If they say that he will overtake the tortoise in a given time, then overtake it he will. If that happens to involve an infinite number of steps of the form 'move to a particular location', then an infinite number of such steps will happen. If it involves his passing through an uncountable infiniy of points, then that is what he does. But nothing physically infinite has happened.

Like scientific theories, policies cannot be derived from anything. They are conjectures. And we should choose between them not on the basis of their origin, but according to how good they are as explanations: how hard to vary.

The Principle of Optimism: All evils are caused by insufficient knowledge.

If something is permitted by the laws of physics, then the only thing that can prevent it from being technologically possible is not knowing how.

The same must hold, equally trivially, for the evil of death - that is to say, the deaths of human beings from disease or old age. This problem has a tremendous resonance in every culture - in its literature, its values, its objectives great and small. It also has an almost unmatched reputation for insolubility (except among believers in the supernatural): it is taken to be the epitome of an insuperable obstacle. But there is no rational basis for that reputation. It is absurdly parochial to read some deep significance into this particular failure, among so many, of the biosphere to support human life - or of medical science throughout the ages to cure ageing. The problem of ageing is of the same general type as that of disease. Although it is a complex problem by present-day standards, the complexity is finite and confined to a relatively narrow arena whose basic principles are already fairly well understood.

SOCRATES: [Gasps.] It is a wonderfully unified theory, and consistent, as far as I can tell. But am I really to accept that I myself - the thinking being that I call I' - has no direct knowledge of the physical world at all, but can only receive arcane hints of it through flickers and shadows that happen to impinge on my eyes and other senses? And that what I experience as reality is never more than a waking dream, composed of conjectures originating from within myself? HERMES: Do you have an alternative explanation? SOCRATES: No! And the more I contemplate this one, the more delighted I become.

In the real multiverse, there is no need for the transporter or any other special apparatus to cause histories to differentiate and to rejoin. Under the laws of quantum physics, elementary particles are undergoing such processes of their own accord, all the time. Moreover, histories may split into more than two - often into many trillions - each characterized by a slightly different direction of motion or difference in other physical variables of the elementary particle concerned.

Thanks to the strong internal interference that it is continuously undergoing, a typical electron is an irreducibly multiversal object, and not a collection of parallel-universe or parallel-histories objects. That is to say, it has multiple positions and multiple speeds without being divisible into autonomous sub-entities each of which has one speed and one position. Even different electrons do not have complete separate identities.

The creators of bad explanations such as myths are indeed just making things up. But the method of seeking good explanations creates an engagement with reality, not only in science, but in good philosophy too - which is why it works, and why it is the antithesis of concocting stories to meet made-up criteria.

The voters are not a fount of wisdom from which the right policies can be empirically "derived'. They are attempting, fallibly, to explain the world and thereby to improve it. They are, both individually and collectively, seeking the truth - or should be, if they are rational. And there is an objective truth of the matter. Problems are soluble. Society is not a zero-sum game: the civilization of the Enlightenment did not get where it is today by cleverly sharing out the wealth, votes or anything else that was in dispute when it began. It got here by creating ex nihilo. In particular, what voters are doing in elections is not synthesizing a decision of a superhuman being, ‘Society'. They are choosing which experiments are to be attempted next, and (principally) which are to be abandoned because there is no longer a good explanation for why they are best. The politicians, and their policies, are those experiments.

The more proportional a system is, the less sensitive the content of the resulting government and its policies are to changes in votes.

The growth of the body of knowledge about which there is unanimous agreement does not entail a dying-down of controversy: on the contrary, human beings will never disagree any less than they do now, and that is a very good thing. If those institutions do, as they seem to, fulfil the hope that it is possible for changes to be for the better, on balance, then human life can improve without limit as we advance from misconception to ever better misconception.

my guess is that the easiest way to signal across such a gap with hard-to-forge patterns designed to be recognized by hard-to-emulate pattern-matching algorithms is to use objective standards of beauty. So flowers have to create objective beauty, and insects have to recognize objective beauty. Consequently the only species that are attracted by flowers are the insect species that co-evolved to do so-and humans.

In the light of these arguments I can see only one explanation for the phenomenon of flowers being attractive to humans, and for the various other fragments of evidence I have mentioned. It is that the attribute we call beauty is of two kinds. One is a parochial kind of attractiveness, local to a species, to a culture or to an individual. The other is unrelated to any of those: it is universal, and as objective as the laws of physics. Creating either kind of beauty requires knowledge; but the second kind requires knowledge with universal reach. It reaches all the way from the flower genome, with its problem of competitive pollination, to human minds which appreciate the resulting flowers as art. Not great art - human artists are far better, as is to be expected.

But the same is true in all art forms. In some, it is especially hard to express in words the explanation of the beauty of a particular work of art, even if one knows it, because the relevant knowledge is itself not expressed in words - it is inexplicit. No one yet knows how to translate musical explanations into natural language. Yet when a piece of music has the attribute "displace one note and there would be diminishment' there is an explanation: it was known to the composer, and it is known to the listeners who appreciate it.

If I am right, then the future of art is as mind-boggling as the future of every other kind of knowledge: art of the future can create unlimited increases in beauty.

Newton's laws are useful for building better cathedrals, but also for building better bridges and designing better artillery. Because of this reach, they get themselves remembered and enacted by all sorts of people, many of them vehemently opposed to each other's objectives, over many generations. This is the kind of idea that has a chance of becoming a long-lived meme in a rapidly changing society. In fact such memes are not merely capable of surviving under rapidly changing criteria of criticism, they positively rely on such criticism for their faithful replication. Unprotected by any enforcement of the status quo or suppression of people's critical faculties, they are criticized, but so are their rivals, and the rivals fare worse, and are not enacted. In the absence of such criticism, true ideas no longer have that advantage and can deteriorate or be superseded.

Memes, like scientific theories, are not derived from anything. They are created afresh by the recipient. They are conjectural explanations, which are then subjected to criticism and testing before being tentatively adopted. This same pattern of creative conjecture, criticism and testing generates inexplicit as well as explicit ideas. In fact all creativity does, for no idea can be represented entirely explicitly. When we make an explicit conjecture, it has an inexplicit component whether we are aware of it or not. And so does all criticism.

The Easter Islanders' culture sustained them in both senses. This is the hallmark of a functioning static society. It provided them with a way of life; but it also inhibited change: it sustained their determination to enact and re-enact the same behaviours for generations. It sustained the values that placed forests - literally - beneath statues. And it sustained the shapes of those statues, and the pointless project of building ever more of them.

*** The ancient Roman ruler Julius Caesar was stabbed to death, so one could summarize his mistake as 'imprudent iron management, resulting in an excessive build-up of iron in his body'. It is true that if he had succeeded in keeping iron away from his body he would not have died in the (exact) way he did, yet, as an explanation of how and why he died, that ludicrously misses the point. The interesting question is not what he was stabbed with, but how it came about that other politicians plotted to remove him violently from office and that they succeeded. A Popperian analysis would focus on the fact that Caesar had taken vigorous steps to ensure that he could not be removed without violence. And then on the fact that his removal did not rectify, but actually entrenched, this progress-suppressing innovation. To understand such events and their wider significance, one has to understand the politics of the situation, the psychology, the philosophy, sometimes the theology. Not the cutlery.

Optimistic opponents of Malthusian arguments are often - rightly - keen to stress that all evils are due to lack of knowledge, and that problems are soluble. Prophecies of disaster such as the ones I have described do illustrate the fact that the prophetic mode of thinking, no matter how plausible it seems prospectively, is fallacious and inherently biased. However, to expect that problems will always be solved in time to avert disasters would be the same fallacy. And, indeed, the deeper and more dangerous mistake made by Malthusians is that they claim to have a way of averting resource-allocation disasters (namely, sustainability). Thus they also deny that other great truth that I suggested we engrave in stone: problems are inevitable.

A solution may be problem-free for a period, and in a parochial application, but there is no way of identifying in advance which problems will have such a solution. Hence there is no way, short of stasis, to avoid unforeseen problems arising from new solutions. But stasis is itself unsustainable, as witness every static society in history.

Strategies to prevent foreseeable disasters are bound to fail eventually, and cannot even address the unforeseeable. To prepare for those, we need rapid progress in science and technology and as much wealth as possible.

I remarked at the end of Chapter 13 that the desirable future is one where we progress from misconception to ever better (less mistaken) misconception. I have often thought that the nature of science would be better understood if we called theories misconceptions' from the outset, instead of only after we have discovered their successors. Thus we could say that Einstein's Misconception of Gravity was an improvement on Newton's Misconception, which was an improvement on Kepler's. The neo-Darwinian Misconception of Evolution is an improvement on Darwin's Misconception, and his on Lamarck's. If people thought of it like that, perhaps no one would need to be reminded that science claims neither infallibility nor finality.

Most advocates of the Singularity believe that, soon after the Al breakthrough, superhuman minds will be constructed and that then, as Vinge put it, 'the human era will be over?' But my discussion of the universality of human minds rules out that possibility. Since humans are already universal explainers and constructors, they can already transcend their parochial origins, so there can be no such thing as a superhuman mind as such.